Lots of people don’t realise that although you may see work by a certain author on the bookshelves in your favourite shop, many writers still hold down a day job in addition to penning their next novel. In this series, we talk to writers about how their current – or previous – day jobs have inspired and informed their writing.

Today, I’m delighted to welcome Jan Fortune to the blog to talk about how she managed to write a trilogy in the last four years while holding down a day job. My thanks to Jan for taking the time to share her insights with us.

Vic x

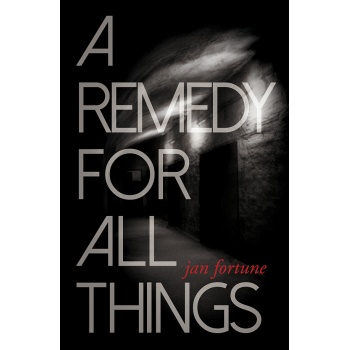

Over the last four years I’ve been working on a trilogy of novels. A Remedy For All Things follows Catherine, who is in Hungary in 1993 to research on the poet Attila József, when she begins dreaming the life of another woman from a different time period (imprisoned after the Hungarian Uprising of 1956). Even more disturbing, she’s aware that the other woman, Selene, is dreaming her life.

It’s a complex book that has taken a great deal of research as well as several edits, but like most contemporary writers, I don’t write full-time. How do we do it? Juggle work, homes to run and still write? And are there any benefits to writing in this way, without the luxury of all the time in the world, or at least all the time that would otherwise go into holding body and soul together?

Many of my favourite writers combined work of all sorts with writing. William Faulkner is reputed to have written As I Lay Dying in six weeks. He claimed that while working 12 hours days as a manual labourer he wrote this phenomenal novel in his ‘spare time’. Most of us need a lot longer, but it’s certainly the case that many writers don’t only write.

Anthony Burgess taught and composed music; Joseph Conrad was a sea captain; T.S. Eliot worked in a bank and Arthur Conan Doyle was a doctor, as was the poet William Carlos Williams. Wallace Stevens turned down a Harvard professorship rather than give up his 40-year career in insurance.

Women who write may not only do the lion’s share of domestic work while writing, but also hold down demanding jobs. Agatha Christie worked as an apothecary’s assistant, a great place to learn about poisons. Toni Morrison worked as an editor and for many years Octavia Butler had to write in the early hours so that she could work low-paid jobs like telemarketing or cleaning.

If working the day job is a necessity, it can also be one with benefits. Working as an editor and publisher, I get a lot of time to see how form works, how language can constantly be honed and how handing our precious book to someone with skill and objectivity and then listening carefully can make all the difference. One of my authors recently took a PR role that is giving her masses of people-watching time, none of it wasted. Writers are people who walk about the world with all their senses open and work is an endlessly rich environment for observation of the human condition.

Of course, we still need time to find that trance state in which to write and to go into deep flow. If your day job does nothing but hollow you out, it may be time to reconsider. But if your work sustains you and leaves the time and energy to write whilst being a source of experiences and characters, then writing around the day job is an honourable tradition.